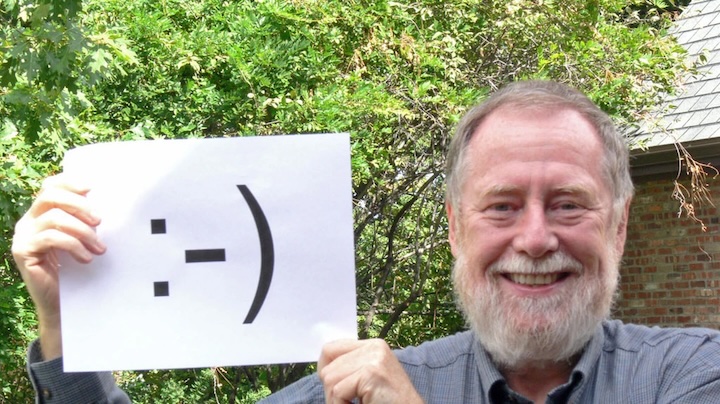

November 11, 2022 — Dr. Scott Fahlman is a Professor Emeritus in the Carnegie Mellon’s School of Computer Science. He is a computer programming language connoisseur and the original neural network jedi master. He was one of the core developers of the Common Lisp Language and his current work includes Artificial Intelligence. Dr Fahlman is as notably kind as he is a humble scientist. Befittingly, he is the originator of the internet's first emoticon, sideway smile :-)

Are there any neat ideas from Lisp that have yet to go mainstream?

Dr. Fahlman: It took a long time for Lisp's automatic storage allocation and garbage collection to go mainstream. This is more than "neat", it eliminates a whole class of bugs that are among the most subtle and difficult to find and fix. But people resisted this as being too inefficient until Java came along and made the idea more mainstream.

The other "neat" idea -- still not "mainstream", as far as I know -- is to represent programs as the same kind of objects that the system is good at manipulating: linked lists, in the case of Lisp. The transformation from text to list-structured representations is trivial (that's why Lisp programs have some many parentheses), and you can run that code directly in an interpreter, or compile it on the fly into fast, efficient machine code.

This makes it possible for Lisp to have a very powerful and flexible macro system, in which programs can easily transform expressions from some surface form to a different internal form. That, in turn, makes Lisp an excellent tool for implementing more specialized languages, with user interfaces that make sense in that domain. Most of the major packages in Common Lisp started out as macro packages, and then the popular ones made it into the language spec: the complex version of LOOP, the complex FORMAT statement, even the Common Lisp Object System.

When you were making programming languages what references did you use?

Dr. Fahlman: I used Maclisp for my grad-school years at the MIT-AI lab (1969-1977), and we had some nice documentation for that. And also the code for the system itself. Or I could go down the hall and talk to the people who had built that system. I briefly used a Symbolics Lisp Machine, and it had good documentation as well. The Sussman and Abelson book, Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, came along later, and was a good intro to the kind of thinking that went into Lisp and the simplified Scheme dialect of Lisp.

I was part of the core design team for Common Lisp (the so-called "Gang of Five") that designed Common Lisp, drawing from all the existing Lisp dialects, trying to find a combination of features that some of us liked and that we all could live with. (DARPA had decreed that they were no longer going to fund the development of many Lisp dialects, so we all had to settle on a "common" one to use going forward.) We had a long design process within the various branches of the Lisp community of the day, and we had access to the code and documents of most of those existing systems. Guy Steele moderated that discussion for a while, and then I took over as moderator.

The resulting specification was written down by Guy Steele, with help from me and a lot of others, and that defined the language: Common Lisp, The Language (Second Edition), known as "CLtL". There was also a formal specification, formulated by the X3J15 committee under the ANSI standards body.

But neither of those documents were meant to be a tutorial or to be very user-friendly. For people wanting to learn Common Lisp, I recommend "Practical Common Lisp" by Peter Seibel, and also keep the Common Lisp Hyperspec handy for specific questions. There are open-source implementations of CMU Common Lisp and Steel Bank Common Lisp out on the web.

In designing Common Lisp, it was all politics. A lot of fairly ugly compromises were required to keep one group or another from walking away. So, while I am overall proud of the result, and it is still the language I use when I have a choice, it lacks the elegance of a language designed by a single person with a single vision. We teamed with a group from Apple to design Dylan as a worthy Common Lisp successor, but that was during the time in the 1990's when Jobs was gone and Apple was struggling to survive. So first they ruined the initially-beautiful design, and then they shut down the project and the Apple lab in Cambridge MA that was working on this.

What would be your advice to young people today who want to get into the field of designing programming languages?

Dr. Fahlman: Don't! Unless you like to do this as a hobby. What I came to understand, after years of work on Common Lisp and the death of Dylan, the ongoing popularity of the hideous C++, and the rise of Java, is that programming languages don't become mainstream based on their elegance or their deep utility. For any given project, the best programming language to use is the one everyone else is using for that kind of programming at that time. It doesn't have to be the language that is best or most beautiful, and it hardly ever is. As long as the currently-dominant language is adequate to the task without TOO many infuriating shortcomings, just use it. You'll be able to hire programmers, get support, have the latest libraries, and so on.

So the best languages very rarely take over, if ever. Some language starts being used because it has the backing of some big company or project, people doing similar things use it as well, positive feedback sets in, and soon it is the language everyone is using. Java is an example -- not nearly as good as Lisp on many dimensions, but it appeared at the right time for a language with some good properties for creating downloadable Internet apps. And it had the backing of Sun Microsystems, at a time when Sun was powerful. So Java became mainstream, while Common Lisp and Dylan faded away. The programming language formalists at CMU, who prefer languages like ML, are constantly disappointed that nobody ever chooses to write programs in them.

So, in the mid-1990s, I decided that I was not longer going to put effort into building programming languages and tools, when the choice of which languages became popular was essentially a lottery. Since then, my focus has been on AI research, and part of that involves the design of planning systems that (maybe) can eliminate the need for most programming. You tell them what you want, as you might describe it to a smart grad student, they maybe ask some clarification questions, and then they go do it. That only works if they know enough about the world and have enough "common sense" to avoid blunders. I still use Common Lisp for developing my AI implementations, but if there is commercial interest I can translate the code into Python or whatever, or hire someone to do this.

Image source. Thank you for your time Dr. Fahlman! :-)